Though he Married the Scythemaker's Daughter,

the Grim Reaper Found him Out:

A True Story from Auburn's Past

by the Reverend Robert C. Ayers

Rector Emeritus, St Peter's Church, Auburn, New York

AS

THE END OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY approached, John Brainard, rector of St Peter's Church, was nearing seventy. His accomplishment in Auburn,

New York was monumental: a parish with few financial problems, a magnificent cathedral-like church and chapel, and many, many of the fine

families of Auburn in his congregation. His second wife, Cornelia, one year his senior, the widow of Waterloo manufacturer Levi Fatzinger,

kept his household running in the old Federal-period rectory next to the church. She had raised his son John Morgan as if he were her own,

and managed his home life as well as his late mother-in-law Mrs. Judson had done in her time.

AS

THE END OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY approached, John Brainard, rector of St Peter's Church, was nearing seventy. His accomplishment in Auburn,

New York was monumental: a parish with few financial problems, a magnificent cathedral-like church and chapel, and many, many of the fine

families of Auburn in his congregation. His second wife, Cornelia, one year his senior, the widow of Waterloo manufacturer Levi Fatzinger,

kept his household running in the old Federal-period rectory next to the church. She had raised his son John Morgan as if he were her own,

and managed his home life as well as his late mother-in-law Mrs. Judson had done in her time.

|

|

(parish archives) |

Few ministers in the Episcopal Church had heaped upon them the memorials and distinctions that John Brainard received in the long years since he came to Auburn in 1863. From the first day it had been an exhilarating experience. On the train from Syracuse he had been accompanied by parishioner William H. Seward, the US Secretary of State, traveling home from Washington to Auburn to visit his sick son. Met at the station by General John Chedell and a large crowd of leading citizens, the little family was conveyed grandly to their new home in the memorable rectory on Genesee Street, Hobart House, as Brainard would later dub it.

Brainard was a man to keep prominent track of his anniversaries, and he reveled in their accumulation. His tenth anniversary as rector would lead on to his glorious twenty-fifth Anniversary in 1888, with its memorial booklet and a grand solid silver Tiffany vase. To mark the close of his thirty-sixth year as rector in 1899, two white oak trees were planted in front of the church. He had known and buried and shared in the honors of two great statesmen, Seward and New York Governor Enos T. Throop. Brainard had been nominated for bishop several times, and while never elected, he enjoyed the distinction. His forte lay in his vocation as beloved parish pastor. He was President of the Standing Committee of the diocese and trusted counselor to his bishop. And he was a Morgan from Connecticut.

'Now King David was old and stricken in years; and they covered him with clothes, but he gat no heat'. First Kings 1:1 Advancing age and the increasing burdens of parish work made Brainard long for assistance, clerical assistance. The time when he had prided himself on the number of services he could conduct on a Sunday was in the past.

Those days when he had taken three services on the Lord's Day, plus a baptism and several funerals—with possibly an evening service at St John's thrown in—all in great stride, seemed to be long gone by. His success was his undoing. The wealthy were content to have their weddings and funerals and baptisms on days during the week.

|

|

(parish archives) |

They took the time out or off as they pleased. But the growing numbers of the middling and lesser sort who flocked to St Peter's because of the services and programs Brainard had helped put in place, these factory and day workers could not afford to take a weekday for their religious practices. They wanted their funerals and the like on Sunday, their day of rest and unemployment. Every year that went by, the journey to a home for a baptism or a funeral, or to the burial grounds of Fort Hill or Soule or North Street, in the rain or snow, felt harder and harder. The oak tree planted in his honor in the churchyard in 1899 grew stronger with each year, but the oak of a man from Connecticut grew weaker.

He began to look about for an assistant, perhaps even someone to take over near

the end. There was no retirement as such possible. Even bishops served until they dropped. Bishops De Lancey and Coxe had soldiered on until

their final breath, confirming and preaching even when too weak to stand, bishop to the end of life. Perhaps John Brainard could engage a

rector co-adjutor, an assistant enticed with the right to succeed him in office?

Then appeared the Chaplain of the Triumph Hose Company No.1. One day

in late July 1900 there appeared in Auburn the Reverend Leonard J. Christler, rector of Calvary Church, Homer, and a native son of Waterloo.[1]

As Chaplain of the Triumph Hose Company No.1 of Homer, he was called upon to make the response to the address of welcome in the first day's

proceedings of the annual Central New York Firemen's Convention.

At the same time Dr. Brainard's journal reads, July 20. Friday: Began morning service in chapel but was taken sick and fainted. July 22. 6th Sunday after Trinity, ill in bed.[2] The 24-year-old visiting fireman/priest was conveniently called in to take the Hutchinson-Guion wedding in emergency, in place of Dr. Brainard who was indisposed.[3] A month later it was announced that Christler had been called to act as assistant rector to Dr. Brainard. He began to help on August 12th, 1900.

|

|

(undated newspaper clipping) |

As the years passed Brainard began to style the young assistant Rector Co-adjutor. Though there is no such title in common use, it certainly carried weight and seemed to secure Christler as the guaranteed legal successor to the old rector. Gradually Christler was taking more and more of the occasional services of baptisms, especially those that were in the home or in the hospital, or of adults. His sister Jessie kept house for him, in their various apartments at No. 16 or No. 4 James Street, where she often stood as witness for the weddings performed in their small parlor.

It is not fair to say that Christler completely took over, but by 1905-06 he was performing eight out of ten weddings, most of the baptisms, and in 1905, all of the funerals and interments. John Brainard was plainly and practically out of commission. When Brainard's wife Cornelia Kern Fatzinger died in 1905, it was Christler who read the burial office. And he also officiated at the 1905 funeral of 81-year-old David Wadsworth, father of David M. Wadsworth, Jr., and grandfather of a recent Wells College graduate, Miss Anna Wadsworth. The Wadsworths, with a fine large home at 186 Genesee Street, were the proprietors of the Wadsworth Scythe Factory on Wadsworth Street.

In April of 1906, Brainard, weaker, scarcely capable of public appearance, having made no entries in his clerical journal since early 1905, announced to the Vestry of St Peter's that he could no longer serve, and that he wished to give up his salary and retire to his lonely rectory. Yet somehow at this extreme, he managed to disengage Leonard Christler from the rectorship of St Peter's Church.

One principal source for understanding why this took place is the account given by the Rev. Arthur Byron-Curtiss in his Reminiscences written in 1950.[4] He describes Leonard Christler in the following unflattering passage.

A 'Rev. Christler' had prepared for orders at St Andrew's Divinity School.[5] He came from a poor family of the village [of Waterloo], and I guess his success in entering professional life, together with a lack of grace, made the dear fellow awfully pompous, conceited and aggressive. He was assistant to Rev. Dr. Brainard—for a while. Dr. B was getting old and somewhat feeble, and Christler just rode over the old rector.[6]

How the break was achieved can be inferred from Brainard's letter in the vestry minutes of April 19, 1906:

Gentlemen, as you are already aware no doubt, the Rev. Leonard J. Christler, my assistant, has resigned, and that his resignation has been accepted, taking effect at the close of the service on Sunday last.

That Brainard had precipitated some crisis to force the young man out, without alienating him fully, is indicated by the subsequent assertion of Byron-Curtiss that the old rector found his dismissed rector co-adjutor a new position appropriate to Christler's talents:

The solution? Montana. In despair, Dr. Brainard appealed to the young man's old rector, Dr. Duff at Waterloo. Between them they got Christler to go to Montana to do missionary work under Bishop Brewer. Bishop Brewer had been rector of Trinity Church, Watertown, and Dr. Duff told the Bishop to call Christler Archdeacon and he would knuckle down and hustle the work. It worked out as they planned, and Christler even called himself by the usual flashy label, of Bishop of All Outdoors.

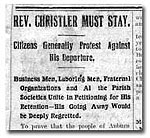

But before Mr. Christler could be fobbed off to Montana, his friends in Auburn put up a struggle. He had joined a variety of fraternal organizations, the Masons, the Elks, and the Firemen. He was in demand as a speaker for these and had circulated widely in Central New York. Immediately that his chute became known, a petition campaign was drummed up in the newspaper [7] and the vestry were troubled with petitions to keep him on, while Dr. Brainard was announcing the assistant's resignation.

Petitions presented on behalf of Mr. Christler were read and referred to the committee appointed to confer with Dr. Brainard, read the Vestry Minutes of April 19, 1906. They were dealt with at the meeting of May 2, 1906: The special committee to whom the petitions on behalf of Rev. L.J. Christler was referred returned them to the Vestry for consideration. Resolved, that it is the sense of the Vestry that the best interests of the Church made it inexpedient to comply with the requests of the petitioners.[8]

|

|

20 April 1906 |

'Mr. Christler can not and must not leave the city' So the reason for excluding Christler from the rectorship was, that active as he might have been, he had worn out his welcome with Brainard, had overreached himself, and was not acceptable to the upperclass professionals and manufacturers who constituted the Vestry of St Peter's, and who now found themselves solely responsible for choosing the next rector. Byron-Curtiss makes clear that the assertive mill hand's son from Waterloo did not know his place. A sure sign of the class conflict inherent in Christler's departure is the nature of his support. In addition to the fraternal organizations who 'say that Mr. Christler can not and must not leave the city, a delegation of laboring men visited Mr. Christler with a petition signed by two hundred laboring men'. The laborers are stated to have offered him 'generous financial support if he would make up his mind to remain among the citizens of Auburn'. 'All the parish societies' are represented as having petitioned the Vestry on behalf of the young assistant, who visited the needy, ministered to the sick in the hospital, and played the Santa Claus to hundreds at Christmas time.[9] The smell of opposition and competition, if not insurrection, was plainly in the air.

But Leonard was wise enough to decline a public reception, 'offered as a mark of the esteem and appreciation in which he is held by the men and women and children in all walks of life'.[10] And the Vestry held firm.

Thus Dr. Brainard was able to live out his years in the rectory until 1909, without having to contend with Leonard Christler's boorish ambition. Instead the vestry found the old rector another assistant in the person of the Reverend Norton T. Houser, rector of East Mauch Chunk, Pennsylvania. Mr. Houser arrived even before Mr. Christler was fully packed and proved himself diligent, professional, and sufficiently reserved to guard his circumstances. When Brainard finally passed away, Houser made it clear to the vestry that he did not feel entitled to become the rector automatically. The vestry elected him anyway.

Meanwhile Leonard Christler took to the West like a duck to water. Centering himself on Havre, Montana, the hub of the High-Line that runs east and west along the Milk River fifty miles or so south of Canada, his fraternal, social ways endeared him to many in the hundreds of square miles over which he ranged. Constantly calling himself the Bishop of All Outdoors, he throve on the role of pioneer, working with the plainsmen, the miners, the homesteaders and railroaders, all of whom like himself he characterized as 'wide between the eyes'. There was room on the plains and valleys of Montana for his ambitious spirit. Over the years he saw the gradual building of a stone church in Havre, the granite for which was hauled free from Helena on J.J. Hill's Great Northern Railroad.[11] From the groundbreaking in 1908 until the first services in 1915 Christler pushed the construction along with a copy of the plans always in his pocket.[12]

But he did not neglect the folks back home. Annually the Bishop of All Outdoors returned to Central New York, where he cut a tall figure at over six feet, with a black coat that reached below the knee, his wealth of dark brown curls crowned by a sombrero that boasted of his Western home, and of his success. 'He was quite a character. Not especially handsome, but you would know who he was if you saw him on the street', said a ninety-eight year old who remembered him from girlhood in Havre.[13]

|

|

(undated newspaper clipping) |

Both flawed for the marriage. In 1914 Leonard Christler returned to Auburn and wedded Anna Wadsworth, the scythe manufacturer's daughter. On October 7, 1914 they were married at her parent's home at 186 Genesee Street by his old rector from Waterloo, R. M. Duff. The actual Rector of Auburn that he might have been, Norton Houser, recorded the marriage in the register of St Peter's Church, just a few steps away. There is no evidence that Houser was invited to the wedding. The witnesses were Thomas J. Walsh and Anna's sister, Mabel Wadsworth Pomeroy. Leonard was 37. Anna was 33.[14]

In a way they both were flawed for the marriage. He, shuffled off to the frontier, still considered pushy, marrying above himself, said Byron-Curtiss; she, no beauty, always in black, probably not enamored of the rough West 'You know, Anna Christler, the wife, was tall, stately and dressed in black. She was not all that attractive. She was a sad looking character'.[15] The Christlers remained childless through the eight years of marriage.

But they had friends, Judge and Margaret Carleton among them. When the Carletons marriage broke up, the Rev. Mr. Christler did his best to counsel Margaret. She was a frequent visitor in the rectory and became familiar with its rooms and contents. As he comforted the estranged wife over a period of time it became evident that Mrs. Carleton had transferred her affections to the dashing minister and that perhaps the feeling was mutual. 'We teenage girls followed his romance with Mrs. Carleton closely. We got a big kick out of that', remembered a Havre woman three-quarters of a century later.[16]

Mrs. Carleton went East for a fortnight to take the waters and lectures of Chatauqua, in search of solace or serenity. When she returned to her hotel in Havre she was said to have been 'acting strangely'. Anna Christler was under no illusions, Margaret was infatuated with her husband and wanted him for herself. Margaret kept hanging around their house, entering it when they were not home.

One evening in October, 1922... One Thursday evening in October 1922, after special services at the church, Anna returned alone to the rectory next door, only to discover that someone was inside. Since Margaret Carleton had previously been observed wandering around and trying to gain entrance to the rectory, and since Leonard had spent part of the afternoon at Margaret's hotel room, attempting to soothe her, Anna called to a neighbor, Lawyer Hogue, to accompany her into her home. There they found an incoherent Margaret tearing up the rector's photograph. The lawyer and Anna persuaded Margaret to leave the house and Anna walked with her to the railroad station where they encountered Leonard putting the evening's guest preacher on the train to Butte. Margaret eventually went off, and about midnight the Christlers walked home to the rectory.

No sooner had they entered the house than Margaret Carleton appeared at the front door and walked in, telling Anna that she now had no place in Leonard's life. The couple attempted to reason with the woman but gained nothing. Leonard announced that he was going to bed and walked toward the bedroom. Anna turned to show Margaret the door. A shot rang out, Anna screamed, a second shot was heard. Leonard lay dead, crumpled in the doorway to the sleeping room, and Margaret, shot through the heart, was dead at his side, inside the bedroom or out. Anna summoned doctors and the police.

That is the account that Anna gave the inquest, at which she was the sole witness. The coroner's jury accepted it and ruled that Margaret Carleton had shot the minister dead and then turned the heavy revolver upon herself and with one more bullet through the heart had ended her own life. Margaret Carleton's mother and the estranged husband, the judge, had another, uglier, version. But in a few days Anna was on her way back to Auburn with Leonard's coffin, all expenses paid by the Masons of Havre, who sent two of their fellow craft to accompany her.

She wired the rector in Waterloo, the Rev. John Arthur, to arrange for a funeral in St Paul's Church. She vowed that she would never leave her husband until his body rested in the grave. She kept her hand on the coffin for the entire sad journey. And she thought.

All the days and nights of the long train trip, she thought. What would become of her now? Her father was dead, her brother near death, her sister married and out of the home. Leonard had given her an identity, he had wooed the tall plain spinster and she had committed herself to him, had given up her identity in Auburn, had exchanged her place as the factory owner's daughter for one in a new town in a new state. Her sister had married a Pomeroy, that was a viable identity in Auburn. What would she be, without Leonard? One thing was certain, his honor and his memory must be upheld. Perhaps he had been incautious with Margaret Carleton, perhaps he had led her on until her fancy evolved into her fatal delusion. Surely it was not just a man who had done that; no, it was a man of God, a servant of the Gospel. Leonard's fault, if it were one, had been to be too good, too open, too warm, too giving of himself. Acting in the spirit of the Gospel had brought him to his death. 'He tried too hard to help people,' she repeated to her sobbing heart, as the wheels of the railroad car clicked off the miles from brown dusty Montana to green verdant Auburn.She would defend and preserve his memory. Her role now was that of the widow of a priest of the Lord. And she looked her best in black.

|

|

near Havre, Montana [Credit: Helmbrecht Studio, Havre] |

The lady in black and the chimney. In Waterloo the incumbent rector, Mr. Arthur, mulled over the appropriate way to deal with the obsequies of this fallen brother.

The papers were filled with what, we must admit, was a juicy story, all the best ingredients of the journalistic stew: sex, religion, and violent death. From Syracuse the cowardly lion, Bishop Charles Fiske, wired that it would be inappropriate for Mr. Christler to have a church funeral. Mr. Arthur decided to overrule that on the scene, reasoning that Christler had not been under any sort of discipline. In consultation with Byron-Curtiss and the Rev. Henry Hubbard of Elmira, Christler's old classmate at St Andrew's, it was determined to give him all the honors of his priestly orders.

And the Masons of Waterloo, learning of the manifest pride Mr. Christler had taken in Montana in his Masonic membership and of the generosity of the Blue Lodge of Havre, concluded to meet the funeral train at the station with a committee headed by the rector of Homer, the Rev. Mr. Pennington, a brother Mason, and to accord the Rev. Mr. Christler all the ceremonies of the Lodge. But before the train arrived and to their dismay, the good Masons of Waterloo discovered that Christler had not paid his dues for fifteen years and had been suspended from their fraternity. For the sake of the feelings of Mrs. Christler, their brothers in the West, and to cover their own embarrassment, they carried on with everything as if all were in order, in the larger spirit of the Fraternity.[17]

The body of Leonard Jacob Christler, Priest, lay in state in St Paul's Church, until four o'clock of the afternoon of Friday, November 3, 1922. Then, with the assistance of the Rev. Henry Hubbard of Elmira, and the Rev. Arthur Byron-Curtiss of Willard, the Burial Office was read by the Rev. John Arthur, Rector, and the interment followed in Waterloo's Maple Grove Cemetery. The new widow took up residence with her widowed mother at 186 Genesee Street, Auburn.[18]

In the late 1920s, little David Hammond, serving the altar of St Peter's at the eight o'clock Communion, was aware every Sunday of a lady, dressed in black, who sat in front of the pulpit, looking directly at the statues of the great preachers carved into its corners. Her eye could rest on St Bernard, who preached a crusade, or it might have preferred Savonarola, who brought about the bonfire of the vanities. At any rate, when he asked his mother about the lady, he sensed a whiff of scandal when she whispered, 'That's Mrs. Christler'.[19]

Hill Top Farm, the partially completed new home that Leonard Christler was building

for himself and Anna, about a half mile south of Havre. Montana, on the Beaver Creek road, was abandoned to the winds and fate. Never occupied,

never lived in, it became a place for partying teenagers. One night it caught fire and burned, completely. All that remained was the tall

rock chimney, with its two fireplaces.[20]

Notes

[1] Born in 1876, Leonard Jacob Christler was the second son of Henry L. and Mary Jane (Riley) Christler of Waterloo. The firstborn, George Washington Christler, arrived in 1876. A sister, Jessie Ann, was born in 1878, another sister, Effie May, in 1881. His brother Charles, born in 1884, was confirmed at St Peter's April 2, 1901, Leonard's first year as assistant. [Brainard recorded Charles confirmation as Charles Willard, although his name appears to have been Charles William.] As a twelve-year-old lay reader at St Paul's, Waterloo, Leonard decided to enter the ministry. Graduating at twenty-one from St Andrew's Seminary in Syracuse, he was ordained deacon October 4, 1896 in Trinity Church, Syracuse. He was then appointed to Calvary Church, Homer, and priested January 11, 1899. He began officially in Auburn on October 15, 1900.

[2] Brainard Journal III, p. 59.

[3] Newspaper Clipping in Journal, 'Assistant Rector for St Peter's'.

[4] Reminiscences of the Diocese of Central New York, 1888-1950, by The Rev. A.L. Byron-Curtiss, typescript dated May 1950, preserved in the Archives of the Diocese of Central New York.

[5] The small diocesan seminary in Syracuse operated for about thirty years, producing 80 graduates.

[6] Ibid., p.17

[7] 'Rev. Christler Must Stay' was the headline in the Auburn Daily Advertiser, April 20, 1906.

[8] The Vestry re-elected for St Peter's Church on April 16, 1906, consisted of three factory owners, three wholesalers, two judges, a lawyer, and the superintendent of the Lehigh Valley Railroad. Five of them lived from numbers 186 to 250 on 'mansion row' on the Genesee Street hill, and four lived within two blocks on fancy South Street.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid. This article in the Advertiser was accompanied by an extravagant three column, twelve inch high, photo of Christler in his robes.

[11] 'Welch's Hi-Line Roofing Secures God's House,' The Havre Daily News, August 6, 1999.

[12] Undated newspaper clipping from Charles Hurlburt's scrapbook, Christler File, Terwilliger Museum, Waterloo, NY

[13] Louise Wigmore, The Havre Daily News, Jan. 3, 2001.

[14] Anna Wadsworth, born July 30, 1881, was the middle child of David M. Wadsworth, Jr. and May Crava Wadsworth. Her sister Mabel was born Feb. 1, 1878 and died in Buffalo May 13, 1940. A brother, David Wadsworth, was born August 6, 1887, and died in Auburn Dec. 14, 1923. David M. Wadsworth, Jr. died in Auburn August 16, 1922, having been a Vestryman of St Peter's continuously since 1901. His wife May died in Auburn July 22, 1935, aet. 77.

[15] Louise Wigmore, The Havre Daily News, Jan. 3, 2001.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Details are from Byron-Curtiss.

[18] In 1926 Anna Christler presented a pair of candlesticks to St Peter's Church, in Leonard's memory, for use on the chapel altar. She later donated a large watercolor of 'Jesus and the Children', framed in polychromed wood, with a brass plate marked with his name and the year 1929. When Anna died in 1940 she was buried in Maple Grove Cemetery in Waterloo, New York, next to Leonard and the Christlers and Rileys. A large marker, topped by a draped fallen cross, seems to have been provided by Anna. Leonard's headstone bears a cross, and hers, a slightly smaller one.

[19] Personal conversation with Dr. Hammond in 1995.

[20] The Havre Daily News, September 7, 2000. Alkali Springs correspondent.