|

||

|

|

Hallo again to all.

We recently had the opportunity to examine a copy of the Polyglot Psalter, published in 1516, touching pages that have the inevitable grime of almost 500 years of fingers. Holding the Psalter in our hands, an odd juxtaposition occurred to us. In many Christian communities around the world, children are taught to sing: Jesus loves me this I know | For the Bible tells me so. Young children are content to know they are loved. But as we gain years, we cloud this simple view with exactitudes: Where, exactly, is it written in the Bible that we are to do this or think that? We begin to treat the text as a technical manual for software beyond our ken. Or we lurch another way and treat the biblical texts as our personal I Ching, certainly a superstitious and unhelpful approach. One way or the other, it's easy to get enmeshed in the text and lose sight of the Word. What to do? Perhaps first realize that our understanding of scripture is highly dependent upon the translation of the Bible available to us. This is not a new dilemma. In the latter half of the fourth century AD, Jerome began and completed a translation of the New Testament and Psalms from the Greek Septuagint and a translation from the Hebrew of the Old Testament. His Latin translations of these became the commonly accepted and authorized version of the Christian Bible for almost a thousand years. Over the centuries Jerome's translation, known as the Vulgate, was repeatedly hand-copied in different monastical scriptoria. Variations and omissions occurred through natural human error and occasional human mischief. These manuscripts then became the source for the next generation of Bibles copied out in each monastery. To a large degree, it was

only the learned elite and the powerful who had ready access to the written word

found in manuscript books. For the common folk, witnessing the reading of the

Gospel with its procession of the elevated Bible was their closest

access to a bound manuscript. With

the introduction of moveable

type in 15th century Europe, all changed. Johannes

Gutenberg's

development of its use in combination with the printing press synchronised

with the desire of religious scholars for deeper understanding of Biblical texts.

Scholars had become increasingly dissatisfied with the many foibles and scriveners'

errors of the Vulgate Bible. One such person

was the brilliant and learned Dominican Agostino

Giustiniani,

bishop of Nebbio on Corsica (1470-1536). Giustiniani

made no little plans. He embarked on an ambitious project: to publish the

Bible in parallel columns from multiple source texts in multiple languages.

(A challenge also for those early typesetters. . .) The first volume would

be the Psalter,

printed in 1516 with permission per

the decrees of the Fifth

Lateran Council. Besides the Latin Vulgate version

of the Psalms, he included Greek, Hebrew with parallel Latin translation,

Aramaic and its corresponding Latin translation, and Arabic sources. Glosses,

or scholarly notes, by the bishop are in an eighth column and also frame the

tops and bottoms of the pages. The bishop ordered what was then a vast number for the printing run of his Psalter: fifty copies printed on vellum and 2,000 printed on paper. He sent the vellum copies to heads of state, but his hope for enough subscriptions to subsidize the publishing of the rest of the Bible failed, and the Psalter remains the only published volume.

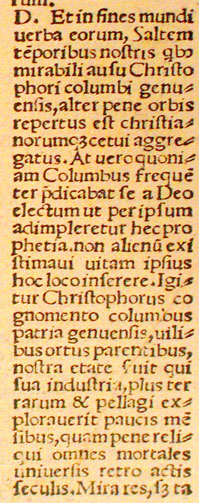

Giustiniani was from Genoa, proud of his heritage and people. A gloss attached to Psalm 19, verse 4, 'yet their voice goes out through all the earth | and their words to the ends of the earth', contains the first printed account of the voyages to the Americas by his fellow Genoan, one Christopher Columbus. In the long note, Giustiniani proclaims that Columbus’ journeys had truly spread the glory of the Lord to the ends of the earth. Alas, Ferdinand Columbus was affronted by the reference to the working-class origins of his father's family. Ferdinand had written his own somewhat vainglorious biography of his father, legitimizing his dubious claim of noble origins. Opting for historical spin and disregarding the immense biblical scholarship in the Polyglot Psalter, Ferdinand snarked that Giustiniani's gloss on Psalm 19 contained 'twelve specific falsehoods' and that the Republic of Genoa had ordered the destruction of the Psalter by public decree. Either this decree was bluster on the part of Ferdinand or the follow-through was lax: a number of copies of the Polyglot Psalter survived. And later research has shown that Columbus was indeed of working-class heritage. The Polyglot is undoubtedly an example of wrestling with words and language to gain a deeper understanding, comparing texts from different sources and discerning meaning through study and discussion. The glosses highlight differences between translations and sources, explaining in detail the gnarly words or phrases. Giustiniani knew that discerning the meaning and wording of the Psalms, both in a contemporary cultural context and in the contexts of the manuscripts of origin available to him for study, required going deeper. In the half millennium since the Polyglot Psalter was published, more ancient scrolls and fragments have been unearthed. And from those scraps and scratches, new translations arise, more accurate than earlier texts. And then those are superseded by even newer translations based on more recent scholarship. So rightly goes the advancement of learning. When someone tells us with great conviction that the Bible 'says so', it makes us tetchy. We hear a shofar trumpeting to proceed with caution. Surely, ultimately, we should lose sight of the text altogether and see only the Word. We know it can be so, from the lives of the saints: the Word itself can be enmeshed in us. Isn't that truly the text that Our Lord proclaimed?

See you next week. |

This web site is independent. It is not official in any way. Our editorial staff is private and unaffiliated. Please contact editor@anglicansonline.org about information on this page. ©2008 Society of Archbishop Justus. Please address all spam to press@anglicansonline.org |