Hallo

again to all. Hallo

again to all.

For years we have been fascinated by plebiscites, large-scale referenda during which people—the plebs—decide by whom or in what way they will be governed. In our lifetime, two of the most memorable plebiscites have been those that led to the creation of Nunavut and Timor Leste as distinct political entities. Plebiscites generally operate with the following framework:

Direct vote by all members of the entire group concerned

Outside monitoring of balloting by an impartial judge or group of judges

Commitment by all sides to honour a legitimate outcome

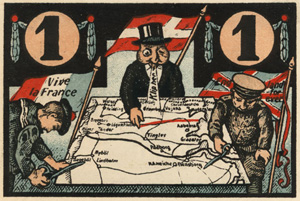

In the early decades of the last century, particularly after the First World War and under the aegis of the League of Nations, plebiscites were a way of establishing what was then called 'self-determination' for people who found themselves in nations for which they had no natural allegiance: German-, Danish-, Polish- or Swedish-speaking minorities, for example, who because of the vagaries of war and cartography were not living in Germany, Denmark, Poland or Sweden. In the early decades of the last century, particularly after the First World War and under the aegis of the League of Nations, plebiscites were a way of establishing what was then called 'self-determination' for people who found themselves in nations for which they had no natural allegiance: German-, Danish-, Polish- or Swedish-speaking minorities, for example, who because of the vagaries of war and cartography were not living in Germany, Denmark, Poland or Sweden.

Plebiscites were and are remarkable instances of reason triumphing over passion in disputes about international sovereignty. One of the most famous such political disputes was resolved through plebiscite in 1920 in Schleswig-Holstein, part of southern Denmark or northern Germany depending on one's allegiance. It was a famously intractable problem, the best summary of which runs like this:

Only three people understood the Schleswig-Holstein Question. The first was Albert, the Prince consort, and he is dead; the second is a German professor, and he is in an asylum: and the third was myself—and I have forgotten it.

Under the watchful eyes of military observers, inhabitants of the two old duchies voted on whether they preferred to be governed by Germany or Denmark. The results were fairly predictable: plebiscite districts with Danish language majorities voted to become part of Denmark, and districts with German language majorities allied with Germany. For a time afterward many people from this beautiful part of Europe believed themselves to be living in the right place. The destinations of taxes, the languages of government, the laws enforced by police and judiciary changed for a short two decades. So did the words of national anthems and the currency and stamps. But in short order one of the great problems of plebiscites became apparent when German tanks crossed the Danish border. The peaceful conflict resolution that plebiscites provide can be reversed more or less immediately by any country with guns whose rulers happen to disagree with its results.* Under the watchful eyes of military observers, inhabitants of the two old duchies voted on whether they preferred to be governed by Germany or Denmark. The results were fairly predictable: plebiscite districts with Danish language majorities voted to become part of Denmark, and districts with German language majorities allied with Germany. For a time afterward many people from this beautiful part of Europe believed themselves to be living in the right place. The destinations of taxes, the languages of government, the laws enforced by police and judiciary changed for a short two decades. So did the words of national anthems and the currency and stamps. But in short order one of the great problems of plebiscites became apparent when German tanks crossed the Danish border. The peaceful conflict resolution that plebiscites provide can be reversed more or less immediately by any country with guns whose rulers happen to disagree with its results.*

We have watched with interest and not a little confusion as Anglican parishes, dioceses and perhaps provinces in some parts of the world have appeared to adopt a plebiscite-based model of church affiliation in recent years. We would like to see all people able to worship freely according to their conscience. We also understand that church history shows us an important model of government and decision-making in the conciliar process during which bishops cast votes for or against critical doctrinal definitions. None of this adds up to a strong case that plebiscites are the normal decision-making process for breaking or establishing relationships of ecclesial communion, and this is because we live in a tradition that accepts and is guided by Tradition. In G.K. Chesterton's memorable words, 'Tradition means giving a vote to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead. [...] Tradition refuses to submit to the small and arrogant oligarchy of those who merely happen to be walking about.' We search in vain for examples of plebiscites in church history; as far as we know there are none to be found, but we hope you will let us know about them if you know better. We have watched with interest and not a little confusion as Anglican parishes, dioceses and perhaps provinces in some parts of the world have appeared to adopt a plebiscite-based model of church affiliation in recent years. We would like to see all people able to worship freely according to their conscience. We also understand that church history shows us an important model of government and decision-making in the conciliar process during which bishops cast votes for or against critical doctrinal definitions. None of this adds up to a strong case that plebiscites are the normal decision-making process for breaking or establishing relationships of ecclesial communion, and this is because we live in a tradition that accepts and is guided by Tradition. In G.K. Chesterton's memorable words, 'Tradition means giving a vote to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead. [...] Tradition refuses to submit to the small and arrogant oligarchy of those who merely happen to be walking about.' We search in vain for examples of plebiscites in church history; as far as we know there are none to be found, but we hope you will let us know about them if you know better.

Chesterton's famous quote cuts in many directions, but it reminds us that the churches in which we worship, and the dioceses and provinces in which they are situated, are things we have received in trust and hope to pass on in trust. Aside from the absence of an impartial monitor for the plebiscite-like votes that have taken place of late, we also lack the crucial participation of that 'most obscure of all classes' and an honest commitment to honour legitimate outcomes. Even taking all these things into account, we hold onto hope that there may be some way of resolving what seem from our limited perspective like intractable problems and disagreements. The knowledge that plebiscites are likely not a route to such a solution does not mean that there can be no solution. It merely challenges us to find another way, if possible a more honourable and religiously consistent way forward. God speed the day of its discovery, and God aid the good people who help to find and craft it.

Chesterton's famous quote cuts in many directions, but it reminds us that the churches in which we worship, and the dioceses and provinces in which they are situated, are things we have received in trust and hope to pass on in trust. Aside from the absence of an impartial monitor for the plebiscite-like votes that have taken place of late, we also lack the crucial participation of that 'most obscure of all classes' and an honest commitment to honour legitimate outcomes. Even taking all these things into account, we hold onto hope that there may be some way of resolving what seem from our limited perspective like intractable problems and disagreements. The knowledge that plebiscites are likely not a route to such a solution does not mean that there can be no solution. It merely challenges us to find another way, if possible a more honourable and religiously consistent way forward. God speed the day of its discovery, and God aid the good people who help to find and craft it.

See you next week.

All of us here at Anglicans Online

|